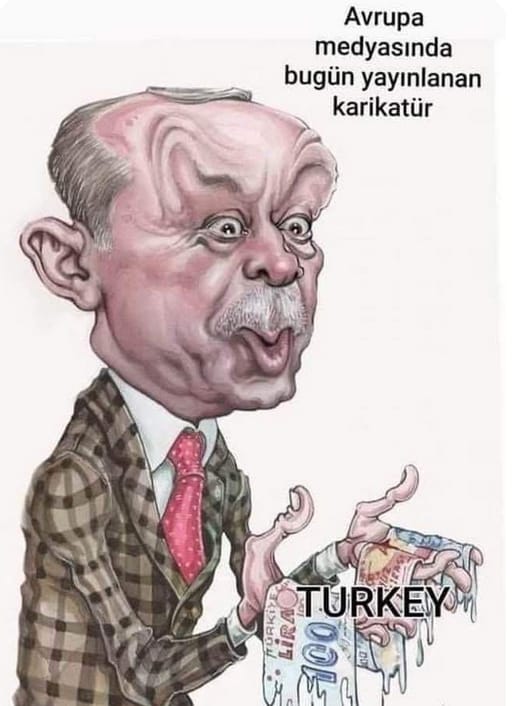

Many Turks feel anxious and ashamed about their eroding living standards, paying the price for President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s past economic missteps even as there are signs that the country is beginning to exit its cost-of-living crisis.

Six years of punishing inflation, combined with a sharp clampdown on credit over the last year, has given retirees and salaried workers a chilling brush with poverty, data shows, testing Turkey’s social fabric more than at any other time during Erdoğan’s more than two decade rule.

Turks say they are now slipping cash to retired parents and grandparents, in a reversal of Turkish custom, even as they themselves struggle to pay monthly bills and forgo modest luxuries such as restaurants.

Erdoğan has urged patience but 2024 is emerging as the most trying in a generation for Turks, whose economic fortunes have rapidly deteriorated since the first in a series of currency crashes in 2018.

“I may still be walking, but I am not really living,” said Fettah Deniz, 73, whose monthly pension of 13,000 lira ($393) is three times below the designated poverty line of a person in his situation, so his children help him out.

At holiday gatherings he has even avoided his grandchild because he had no extra cash to give – “the plight of many honorable and traditional people in our society,” said Deniz, who helps run a retirees association in Istanbul’s working class Bayrampaşa neighborhood.

Another retiree, Mustafa Yalçın, 69, said he stayed overnight in a hospital during a trip to Gaziantep because he couldn’t afford a hotel and didn’t want to burden relatives there who would feel obliged to feed him.

The government proposed a boost this month that should raise the average monthly pension to about 14,000 lira from 12,000.

More than half of workers meanwhile live on or around the minimum wage of 17,002 lira, which is not expected to rise despite calls from the political opposition.

That compares to an estimated poverty line that has shot up to 61,820 lira ($1,870) for a family of four in Ankara, Türk-İş, a top union, said in a report last month. Another union, DİSK, found that last year’s average pension was one-sixth of those in central European countries.

Such hardship could erode support for Erdoğan, pollsters say, especially after pensioners helped hand his conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) its worst ever loss in March local elections.

As the economy slows further and employers trim jobs as expected in coming months, it could also test Erdoğan’s patience with the turnaround programme that he launched last year when he picked Mehmet Şimşek as finance minister.

Since June 2023, the central bank’s new leadership has hiked interest rates from 8.5% to 50% – the highest in emerging markets – in order to cool inflation that topped 75% in May.

It’s a shock reversal of the preceding five years in which Erdoğan – describing himself as an “enemy” of interest rates – pushed an easy-money policy to boost economic growth despite soaring prices, and sacked five central bank governors.

Largely as a result of this unorthodoxy, the lira shed more than 85% to the dollar since 2018, foreign investors mostly fled the country and FX reserves touched all-time lows before finally rebounding this year.

Erdoğan has repeatedly backed the new programme, while the central bank says rates will remain high. Analysts say inflation began what will be a sustained fall in June, while ratings agencies have upgraded Turkish assets and many foreign investors have returned.