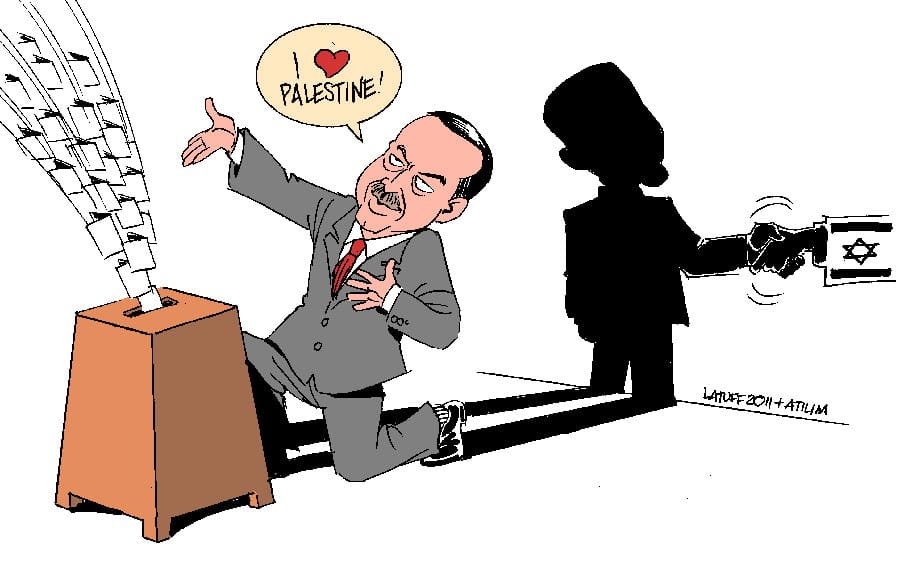

How is it possible that althougth Israel occupation policy lasts for many years – Turkey stil have such a warm realations with Israel? apperently Erdogan knows how to sound threatening but in reality money speaks louder.

On 7 October 2023 when Hamas launched its unexpected attack, Turkey and Israel were during a process of reconciliation, after more than a decade of uneven relations bordering at times on divorce before entering laborious periods of reconciliation. The capacity to manage this volatility is the first source of surprise. It is due to multiple convergences, political, strategic and above all economic. What is the future of this complex relationship in view of the new situation brought about by the return to centre stage in the Middle East of the Israel-Palestine conflict?

To understand how Turkish-Israeli relations have survived and been regularly revived, it is important to identify what it is that has structured them enduringly. The solidity of their economic ties constitutes the first axis of that continuity. As proof of this, we need only remember that during the conflictual years that we have just described, Turkey tripled its exports to Israel, which roos from 2.3 billion dollars in 2011 to 7.03 billion in 2022. Providing 5.2% of the country’s imports, Turkey is thus Israel’s fifth-largest supplier and its seventh-largest customer for 2.2% of its exports, to the tune of 2.5 billion dollars per annum. These trade relations concern vital domains. Heading the list of Israeli importations from Turkey are steel, iron, textiles, motor vehicles and cement, not to mention the Azerbaijani oil which transits via the Caucus and Eastern Anatolia through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline (BTC) to Ceyhan harbour and covers 40% of Israel’s annual consumption of brut. The Turkish corporation Zorlu also provides 7% of Israel’s electricity. As for Israel, its exports to Turkey consist mostly of chemical products and high-tech equipment. These have played a substantial role in the modernisation of Turkish industrial production over recent years, especially in the manufacture of armaments.

More recently, in January 2024, Turkey took Israel off the list of countries it targets for export. This decision deprives Turkish companies of State aid for exports to that country. It shows the leeway Turkey now enjoys on the booming export market but does not call into question very deeply its bilateral trade relations. At the end of January 2024, the Transport Ministry statistics showed that 700 Turkish ships had put in at Israeli ports since 7 October 2023, i.e. an average of 8 ships per day. Their cargos consisted of such essential products as steel, oil, and textiles for the Israeli war machine and involved companies often closely associated with Turkish circles of power, ‘underlining’, according to independent Turkish journalist Metin Cihan 3‘the hypocrisy and double speak of the country’s rulers.

The stiffening of the Turkish position after the start of the Israeli attack on Gaza and the many Palestinian civilians killed has enabled the regime to keep pace with the emotions experienced by the Turkish population. This is more important for the AKP as there are to be local elections on 31 March 2024 at which time Erdoğan hopes to win back the symbolic cities of Ankara and Istanbul, lost in 2019. However, it is unlikely that this stiffening will result in a reconsideration of the existing economic ties between the two countries, or by an official breaking-off of diplomatic relations. Basing itself on the experience of crisis management acquired over the past two decades, Ankara will probably tend rather to limit the scope of its trade relations with Israel, attempting to compensate for this through the renewal, already under way, of its relations with the Gulf countries (Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, in particular) as well as with Egypt.

If Erdoğan gets over the hump of the Spring elections, he should be able to resume a more diplomatic posture, arguing that he can serve the Palestinian cause better by siding with other regional powers more deeply committed since the crisis began (Qatar, Egypt, United Arab Emirates…). Such an attitude would not in the long run be so remote from that felt by a public opinion which is also ambivalent, and which began by being very wary of Turkey’s committing itself too deeply and did not in its majority approve of breaking off trade relations with Israel. It is therefore likely that the regime will rely upon an array of contradictory interests and sentiments to maintain that ambiguous relationship with Israel, which has been kept alive for such a long time.